In this blog post, we’ll profile the most important metrics to track and measure when assessing the health of a software-as-a-service (SaaS) company.

While there are many financial metrics investors look at, SaaS metrics are tailored to the unique attributes of software companies. They can tell you a lot about how a company is performing and where it’s headed.

That’s why we’ll discuss how investors and entrepreneurs can calculate and use these critical metrics to make informed decisions!

Read on to learn about the key SaaS metrics.

What are SaaS metrics?

Saas metrics are important performance indicators that help measure the health of a SaaS company.

Key business areas that SaaS metrics are used to measure are efficiency, growth, retention, customer satisfaction, and more.

They help investors and entrepreneurs track how well software is being used, identify areas where users are struggling, and determine whether investments in SaaS companies or products are paying off.

Which SaaS metrics are most important?

The top SaaS metrics are the following:

- Average revenue per user (ARPU)

- Annual contract value (ACV)

- Churn rate

- Expansion revenue

- Net retention rate (NRR)

- Annual recurring revenue (ARR)

- Customer acquisition cost (CAC)

- CAC payback period

- Customer lifetime value (CLV or LTV)

- LTV-to-CAC ratio

- Rule of 40

- SaaS magic number

- Burn multiple

I’ll cover each of these metrics, how to calculate them, and why they are important in the sections that follow.

The right SaaS metrics will allow the company to make key decisions, effect changes, and set the company on the right trajectory for the future. They will enable investors or owners to track company progress and make informed recommendations for future company strategy.

The most important SaaS metrics track growth, customer retention, and efficiency. These are the metrics that will help you make the right decisions for your business to grow.

- Growth – rapid year-over-year growth is essential to maintaining market leadership in some of the fastest-growing market sectors.

- Customer retention – higher customer retention decreases the costs of constantly acquiring new customers, and makes each customer more profitable to the business

- Efficiency – metrics tracking efficiency measure how well a business is conducting its retention and growth activities. For instance, are retention and growth happening at an unsustainably high financial cost, or is the company managing its expenses and cash flow well?

Some of the metrics we’ll discuss here are better suited to internal decision-makers, whereas others on the list are more often used by growth or venture investors in making investment decisions.

How is SaaS quality measured?

SaaS metrics are used to assess the strength and overall quality of a SaaS company.

At a high level, the best SaaS companies have high growth, profitable customers, low churn, high retention, and efficient marketing spend.

Each of these criteria, however, can be broken down into specific metrics to measure performance.

SaaS metrics interview questions

Investment firms (e.g. venture capital, growth equity, and private equity firms) are increasingly interested in companies with a SaaS product and business model.

For this reason, I recommend interview candidates applying for jobs at these firms – or SaaS companies – study and understand the definitions of top SaaS metrics when preparing for interviews.

In this article, I’ve detailed many of the top metrics to know. As a base, it’s recommended that you be able to answer the following questions for each metric:

- How do you calculate X metric? What is the formula?

- What are the positives and negatives of looking at X metric?

- What does X metric tell you that Y metric does not?

- What is a “good” level for X metric? What is a “bad” level?

- What top metrics would you use to evaluate X software company?

These are some of the top interview questions covered on SaaS metrics for investment roles and for operating roles.

However, to go into further detail on how these metrics may be tested in your interviews, including case studies, check out my full online interview course.

Average revenue per user (ARPU)

The first metric we’ll look at is average revenue per user. The basic ARPU calculation is straightforward:

Total revenue / Total users = Average revenue per user

Be aware that if the company offers a free version of the software, the free software users can skew the average revenue per user downward.

In this case, the ARPU calculation is modified to exclude nonpaying customers. The formula then becomes:

Total revenue / Total paying users = Average revenue per paying user

Companies use this metric to determine how much value each user brings to the business. If revenue is low, then companies can use this metric to determine if they need to increase the number of users or increase the value each user brings to the company.

Low revenue with a decent ARPU will signal a need to bring in more users, perhaps through higher marketing expenditures. If the ARPU is low, the company might avoid making large expenditures that do not bring significant value to its users. Instead, the company might focus on value-added activities that will enable them to charge more for their software through add-on services.

Companies and investors also track ARPU year-over-year. An increasing ARPU can indicate a healthy customer base, a lessened risk of competition, an increasing price with opportunities for cross-selling and add-ons, and more.

Decreasing ARPU can show poor value proposition with customers, a customer base with low spending power, increasing competition, low product differentiation from competitors, or other market issues.

Investors often use ARPU as a quick and dirty gauge for how well a SaaS company is monetizing its customer base.

SaaS annual contract value (ACV)

Annual contract value is a metric for SaaS companies to measure the yearly value of contracts. It is especially helpful for companies that offer multi-year contracts.

Total booking value of contract / Number of contract years = Annual contract value

Instead of monthly or annual contracts, SaaS companies may offer multi-year contracts for large enterprise clients. For example, a company may have a 5-year service contract at $20,000 per year, with a 15% discount over the total cost because they chose the 5-year package over the 3-year package.

This would yield an $85,000 total contract value. Spreading this contract value over 5 years would result in a $17,000 annual contract value.

ACV does not have to be viewed on a per-contract basis; you could also study ACV for all customers across the company or for a specific time period.

Investors and managers often use the ACV to quantify or benchmark the overall value provided by the company to its customers over a fixed time period.

To go deeper, check out my dive into annual contract value here.

Revenue Churn Rate

Churn (or its inverse, retention) is perhaps the most underrated and important metric in all software companies. If you can’t hold onto customers, it becomes extremely difficult to grow quickly.

The revenue churn rate is one way to measure churn. It measures how much revenue from existing customers returns every month.

To calculate the revenue churn rate, start with the ending recurring revenue for the period. Subtract any new subscription revenue added during the period, and divide the result by the beginning recurring revenue.

Revenue churn rate =

(Recurring revenue for current period – New recurring revenue added in period) / Recurring revenue from prior period

For example:

- Beginning recurring revenue: $10,000

- New subscriptions added: $3,000

- Ending recurring revenue: $12,000

In this example, the company’s metrics indicate a revenue churn of $1,000 and the revenue churn rate would be 10%.

Even though they had greater revenue overall, they lost some older customers. The pre-existing revenue loss is specifically what the churn rate looks at.

If a company has a high churn rate, it can be a sign of a serious business challenge, namely that customers are not happy with the service and are leaving over time (customer churn).

Revenue churn rate should be measured alongside customer churn rate since different customers can bring different amounts of revenue to a company.

For more on churn, check out my dive into net retention rate (NRR) vs. gross retention rate (GRR).

Customer Churn Rate

Since SaaS companies are heavily subscription-based, customer churn is a critical measure of both company health and how successful the company will ultimately be.

Measuring customer churn is fairly simple. Here’s the formula:

Customer churn rate =

(Subscribed customers at end of current period – Subscribed customers added customers in current period) / Subscribed customers at end of prior period

Here’s an example:

- Ending # of customers for current period: 100

- Ending # of customers for prior period: 95

- # of customers gained during period: 10

The customer churn rate is a measure of how many customers were retained from the end of the last month.

Since the company lost 5 customers overall, and gained 10 new ones, they must have lost 15 customers from the beginning of the month, leading to an overall churn rate of 85%.

A low customer churn rate means a loyal customer base and a valuable product. A high churn rate would indicate dissatisfied customers, a high number of competitors with analogous products, or both.

Expansion revenue

Expansion revenue measures how many new purchases or add-ons existing customers made after their base purchase.

Expansion Revenue = Revenue from cross-sells and upsells to existing customers

In the most compelling companies, long-term customers tend to spend more over time. This is because the company finds a way to provide more value to them.

Loyal customers also already know that you have a good quality product and good customer service, so they are more willing to buy other products, services, add-ons, or higher-tier subscriptions.

This creates a more valuable customer and boosts ARPU, ACV, and ACLV metrics.

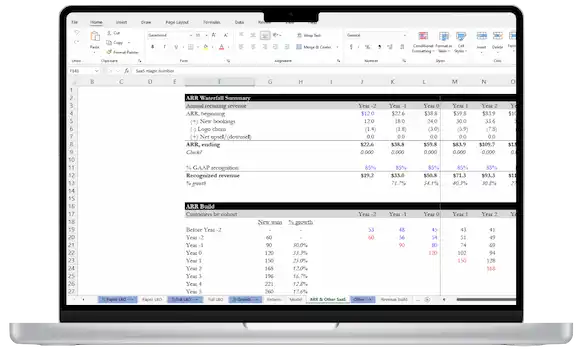

SaaS annual recurring revenue (ARR) or monthly recurring revenue (MRR)

Since the lifeblood of SaaS companies is subscription revenue, annual or monthly recurring revenue is a critically important metric.

While a software company may have one-time revenue sources (such as licenses, onboarding fees, or one-off services), its main revenue is recurring subscriptions.

Monthly recurring revenue shows how many customers keep coming back every month or year after their initial commitment.

ARR = Total Revenue – Revenue from one-time purchases

Annual recurring revenue can show you how many customers (and their spend) are likely to keep coming back year-over-year, assuming no churn, etc. ARR and MRR are usually expressed as a dollar figure.

It is critical to keep total MRR and ARR increasing over time, as a software company. This means that the company’s products are resonating with customers, who are committing to purchase on a recurring basis.

Especially if the company has low churn, growing MRR and ARR also means the company will likely have attractive unit economics or customer profitability. This is because, with recurring revenue, you only pay the cost to acquire the customer once, but you get recurring revenue over a long period of time.

For more, check out this deep dive into ARR and MRR for SaaS.

Net dollar retention (NDR) or net retention rate (NRR)

Net dollar retention (NDR), which is sometimes called the “net retention rate” (NRR), is another measure of how well a company keeps its customers and its subscriptions.

It measures how much annual recurring revenue has grown or shrunk over the course of a year.

To calculate NDR, start with the beginning annual recurring revenue, add new subscriptions and subtract any churn to obtain the ending recurring revenue. Divide the ending recurring revenue by the beginning recurring revenue to obtain the net dollar retention rate.

NDR = (Beginning ARR + Expansion revenue – Lost recurring revenue) / Beginning ARR

Net dollar retention is important to give companies and investors a picture of how well a company keeps its customers and increases the value of each customer.

Gaining new customers is expensive, so it is critical to retain as many customers as you can. NDR gives you a holistic view of customer satisfaction and revenue growth in one metric.

Go here for a deeper dive on net revenue retention.

Customer acquisition cost (CAC)

Customer acquisition cost is a measure of how much a company has to spend to acquire one new customer, whether through marketing, referrals, or some other method.

This is an especially useful metric for growing companies who are still trying to penetrate a market and win a large customer base (i.e. early or growth stage); however, it’s also a fundamental metric that’s relevant to the health of all businesses, no matter the stage.

To calculate CAC, you need to identify each expense that directly brings customers to your business. Include advertising, selling & marketing expenses, discounts or rewards for referrals, and any other customer acquisition methods you have.

CAC = All marketing-related expenses in time period / Number of customers acquired in time period

For example, if you conduct a marketing campaign for a total cost of $500,000 that brought 1,000 new customers to your business, the CAC for that particular campaign would be $5,000 per customer.

Many investors ask entrepreneurs to break down CAC by marketing channel, in order to see which one was most cost-effective or which brought in the customers most efficiently.

- 33 lessons

- 8+ video hours

- Excels & templates

Customer acquisition costs (CAC) payback period

This metric is an offshoot of the previous one.

Once you have the customer acquisition cost, you can use the customer acquisition cost, your average MRR per customer, and your gross margin to calculate exactly how long it takes before each customer provides enough revenue to offset the cost of onboarding them.

The calculation is as follows:

CAC payback period = CAC / (MRR x Gross Margin %)

Therefore, if you paid $3,000 to acquire a new customer, the average MRR per customer was $500, and your gross margin is 90%, your customer will “break-even” approximately 6.67 months after onboarding ($3,000 / ($500 * 90%).

Minimizing the CAC payback period is critical to maintaining profitability and accelerating long-term growth. The shorter your CAC payback period the more quickly you can “recycle” your marketing dollars into acquiring new customers.

Think about it: if you had a CAC payback period of “zero.” This isn’t actually possible, but let’s imagine as soon as you spend dollars on marketing, you near-instantly made your money back in gross margin from the customer. This would mean you could “re-use” that money you just made into acquiring more and more customers.

Many focus on LTV-to-CAC (discussed more later) as the primary metric of unit economics, but now you can see now that CAC payback is also a critical metric for determining the health of your customer acquisition and efficiency of growth.

To learn more, here’s my in-depth guide to the CAC payback period metric.

Customer lifetime value (CLV or LTV)

Customer lifetime value, sometimes simply lifetime value (LTV) describes the total dollar value of each customer over the course of their business with you.

Calculating customer lifetime value can be a bit of a process, as you need to calculate some of the other metrics first.

LTV = (ARPA x Gross margin percentage) / Churn rate

The first piece of the puzzle for CLV is the customer churn rate.

You then calculate the customer lifetime rate by dividing 1 by the churn rate. For example, if your churn rate was 5%, then your customer lifetime rate would be (1/0.05) or 20.

Next, you need your annual gross margin per customer account. You can start with the annual revenue per account (ARPA). Since we want the gross margin, we can use the gross margin percentage of your business to reduce revenue per customer to gross margin per customer.

If your revenue is $500,000 and you have 10,000 customer accounts, your ARPA is $5,000. If you have a gross margin of 85%, your gross margin per customer would be $4,250.

Finally, you can multiply your customer lifetime rate by the annual gross margin contribution per customer to obtain the lifetime value per customer. In this example, the CLV would be 20 x $4,250 = $85,000.

This is a simple estimation of CLV. If you have a wide range of customer values – free version users and high-end enterprise clients – you will need to drill down your ARPA numbers to specific categories of customers, as the lifetime value of each customer will vary greatly.

Also, this calculation shows how to calculate LTV across an entire company or customer base. However, note that LTV is often applied to specific cohorts or groups of customers to be even more meaningful or useful for comparison.

To go deeper, here’s a detailed breakdown of customer lifetime value (CLV or LTV).

LTV-to-CAC ratio

This metric neatly combines several of the others we’ve discussed. This metric helps compare the lifetime customer value to the cost to acquire that customer.

LTV-to-CAC ratio = Customer lifetime value / Customer acquisition cost

This metric helps investors and entrepreneurs determine the “unit economics” or “unit profitability” of their company.

When applied to specific growth channels (rather than overall to a company), it can also be used to determine which customer acquisition methods lead to the most overall value to the company, and where to direct your marketing efforts to obtain those results.

The “ideal” LTV-to-CAC ratio is more than 3:1 or 3.0x – so the customer should bring at least 3 times the value to the business than it cost to acquire that customer.

A higher ratio is almost always better; however, a high LTV-to-CAC can mean that you are putting too much emphasis on existing customer retention and not giving enough attention to growth.

Too low of an LTV-to-CAC ratio, on the other hand, means that your customers are not returning enough value to the business to compensate for the customer acquisition costs.

Since this ratio is one of the most comprehensive metrics we’ve looked at, covering aspects of growth, customer retention, and efficiency in a single metric, it is worth consulting it regularly when evaluating a business.

Sudden changes to either half of this ratio can signal a problem or a market shift worth addressing.

Rule of 40

This “golden rule” of SaaS states that in order to be efficiently run, the company’s growth rate percentage plus its profit margin percentage must be at least 40%.

Annual growth rate % + Profit Margin % = 40%

The profit margin percentage is usually based on EBITDA. While SaaS companies usually use ARR as a measure of financial health, using EBITDA means that you can use this metric to compare the efficiency of companies across stages of growth.

If some companies have slower growth, they should have HIGHER margins. And vice-versa, a company could have lower margins if it is fast growing.

The nice thing about the Rule of 40 is that it can suit both young and old companies. If the Rule of 40 isn’t adding up, CEOs and boards can make strategic decisions about how they want to increase one or both metrics.

Read more about the Rule of 40 in this deep dive.

SaaS magic number

The “SaaS magic number” is kind of like the customer acquisition cost payback period (covered above), except it is a broader catch-all.

Ultimately, the magic number measures how long it takes for the company to recoup the cost of marketing spending from the new business it generates.

To calculate the magic number, you take the difference in revenue between two consecutive quarters of sales and multiply it by 4 (since there are 4 quarters in a year). This number is divided by the marketing expenditure in the earlier quarter.

SaaS magic number = (Sales in current period – Sales in prior period) x 4) / Marketing spend in prior period

For example, if your company made $30,000 in sales in Q1, $40,000 in sales in Q2, and spent $25,000 in marketing in Q1, then the magic number calculation would look like this:

((40,000-30,000) x 4)/25,000 = 1.6

Intuitively, a SaaS magic number of 1.0 means that your payback period for marketing expenses is exactly one year.

A SaaS magic number of greater than 1.0 means that your marketing is very efficient, while a SaaS magic number of less than 1.0 means that your ROI on your marketing will take more than a year and is not considered efficient.

Go here for more on the SaaS magic number, including full examples.

Burn multiple

The burn multiple is similar to the SaaS magic number, except that instead of tracking just marketing efficiency, it tracks overall efficiency.

The “burn multiple” is a measure of how much each dollar invested into the business translates into an increase in ARR.

This is an especially useful metric when measured alongside the annual growth rate, as it shows you how much the company invested for every dollar of ARR growth it achieved.

To calculate the burn multiple, you first have to know the “cash burn,” which is a measure of how fast a company spends its cash – specifically, how much cash it loses every month. A month with positive cash flow is a month with a negative burn.

As an aside, knowing your burn rate is critical in the early stages of a startup, when you’re spending more money than you are making and losing (or burning) cash every month. For example, if you have $10,000 in cash set aside at the beginning of your business, and you lose $1,000 per month, you have a cash burn of $1,000 per month.

The other factor is the net new annual recurring revenue. The burn multiple is the burn divided by the net new ARR, as follows:

Cash burn / Net ARR added = Burn Multiple

A burn multiple of less than 1.0 is ideal, as it shows that the company is generating more than a dollar of new revenue for every dollar spent in the business.

Burn multiples over 1.0 are sustainable for a while if new equity or debt funding structures are always available. However, it can be dangerous to run a company in this way since new funding sources can dry up and investors may lose interest.

Here’s a deeper look at SaaS burn multiple metric.

Revenue recognition for SaaS companies

SaaS companies have quite complicated revenue.

That is, they have recurring revenue (ARR or MRR), but they also have one-time upsells, downsells, expansion, onboarding fees, etc.

Standard accounting requires that all revenue be recorded when it is actually earned. This can present a challenge for SaaS companies, since often they are taking payments for services they have not yet provided (e.g. an upfront payment for a 12-month plan).

As a result, the accounting body that controls standards Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) created ASC 606.

This rule actually applies to all companies, but it is specifically helpful to SaaS companies trying to determine revenue recognition.

ASC 606 includes 5 steps to correctly assign revenue to the right period:

- Identify the contract

- Identify the performance obligation(s)

- Identify the transaction price

- Allocate the transaction price

- Recognize allocated revenue

Go here for in-depth examples of how ASC 606 and SaaS revenue recognition work.

Bookings vs. billings vs. revenue

One source of confusion with SaaS metrics also involves: how bookings turn into revenue, from an accounting perspective.

Well, first let’s start with defining bookings. Bookings are the total deal value that a customer signs up for across the life of a contract. For instance, you might sign a customer to a 4-year deal that will pay $4,000,000 total over the life of the deal ($1,000,000 per year).

When the deal is signed, the company’s bookings are increased by +$4,000,000. However, this does NOT mean that revenue increases by this amount (yet). A few other steps need to happen first.

First, revenue is recognized as the service is provided (as described above). So 1-year into the contract, the company would have recognized $1,000,000 in revenue.

Second, there’s cash flow dynamics associated with these bookings and revenue — that’s where billings come in.

A billing occurs when the company “bills” or asks for cash payment from the customer. This can occur upfront, monthly, annually, or on any schedule dictated by the contract.

In most cases, when a company bills the customer, it creates an accounts receivable which is later extinguished when the customer forks over the actual cash payment. In some cases, if a customer doesn’t actually pay, it could result in “bed debt expense.”

In summary, bookings are total future revenue (expected to be recognized) and revenue is recognized when services are rendered.

On the other hand, billings result in the cash payment from customers related to those revenues.

For more, see my in-depth article on bookings versus billings versus revenue for SaaS.

Accounting standards for SaaS companies

A couple factors make accounting for SaaS companies (somewhat) unique and challenging:

- Subscription revenue over long periods of time

- Cash flow conversion from bookings to revenue & cash flow

- Relatively high margins

Note some or all of these characteristics is present in other industries; however, these issues are certainly present in many SaaS companies.

To deal with these and other accounting complexities, public SaaS companies adhere to GAAP in their official financial statements on an accrual basis (like all companies).

Here’s more info on SaaS accounting standards if you’d like to go deeper.

Tips for improving SaaS metrics

The SaaS metrics covered here describe and measure three key areas of any SaaS business: growth, customer retention, and overall unit profitability.

Want to know how to improve one of your core metrics? Understanding exactly what each metric means to your business is the first step to knowing which area in your business to improve:

- Annual revenue per user (ARPU): To improve ARPU, find ways to upsell or cross-sell products or services to existing customers. This makes each one more valuable to your business. For instance, if you have a generous free version of your plan, free-version users may also be reducing your ARPU as they bring no income to your business. If your company is committed to providing these free resources to small business owners or freelancers who could not afford a high-end software package, simply exclude these free-version users from your ARPU calculations. This will give you a better idea of how much value your paying customers bring you. However, if your free-version users are simply not motivated to become paying customers, you may want to downgrade your free version features to incentivize those users to become paying users.

- Churn rates: Reducing churn is all about customer satisfaction. Providing the best customer experience possible through high quality product/service, responsiveness to requests, and bug-free software is the key to customer retention. Cross-selling may also be a useful churn reduction tool. The more products, services, and tools a customer uses from your company, the less likely they will be to expend the time and energy needed to switch all of their processes over to a competitor’s software.

- CAC and CAC payback period: High customer acquisition costs mean a lower financial return on each customer. To lower your CAC, and thus your payback period, conduct some marketing analysis to see which customer acquisition method brings the highest number of new customers for the smallest budget, and focus more of your marketing methods in that area. Is it more cost-effective to conduct a new digital ad campaign or to reward existing customers with a referral bonus? How about a free trial or low-cost access to a beta version of the product? Which brings in more customers? New SaaS companies may have to settle for a higher CAC in exchange for faster growth, whereas well-established companies with some name recognition will be able to use some of the cheaper customer acquisition methods. A good rule of thumb is to be sure you recoup costs on customer acquisition within the first year.

- CAC-LTV ratio: There are two ways to increase this ratio: reducing the CAC and increasing the LTV. Since we already discussed some ways to reduce the CAC, we’ll take a look at some of the ways to increase the LTV, or lifetime value of each customer. Since LTV is a combination of a few other key metrics, it can be improved by changing those other key metrics in the business. LTV can be improved by reducing churn or by increasing the gross profit per customer. Specific tips include nurturing your email list to increase brand awareness and create warm leads, increasing your lead conversion rate, and making the customer onboarding process as streamlined as possible.

- Rule of 40: To help a company meet the Rule of 40, they have to have a profit margin and a growth rate percentage that add up to at least 40. If the company is not currently achieving that, it can choose whether they need to improve its profit margins through expense reduction or improve their growth rate through new marketing efforts. Since reducing expenses often reduces growth capabilities, and increasing growth often means higher expenses, these metrics can be mutually exclusive. However, a company can obtain better metrics in both areas through careful strategic planning.

- SaaS magic number: A higher magic number is achieved by more efficient marketing campaigns. Similar to the CAC improvement strategies, the company must find a growth strategy that pays for itself in the least time and focus more of its efforts there. The ideal SaaS magic number is cost recovery in less than a year.

Improvements to any of these SaaS metrics can signal a major improvement to the core business. All of these metrics are critical and a healthy business must be sustainable across all these areas, especially customer retention and unit profitability.

SaaS Metrics 2.0

As you can see, there are many top SaaS metrics that investors and entrepreneurs need to know. Knowing these metrics can be helpful in running your business and in interviews with software investment firms.

New metrics are created all the time as business models evolve, so it’s important to stay up-to-date on the latest trends.

If you’re looking for more help preparing for your next interview, check out my full course on growth investing. It covers all the key topics to nail your interviews for growth or late-stage venture capital investment firms.

Or, if you’d like to go even deeper into SaaS, reserve your spot in my online course on SaaS metrics and financial modeling. Enrolling now!

SaaS & Growth Metrics

SaaS & Growth Metrics Break Into Growth Equity

Break Into Growth Equity